Table of Contents

The Birth of Atomic Theory

The idea that matter is composed of fundamental, indivisible units traces back to Democritus, a Greek philosopher who, in the 5th century BCE, introduced the concept of atomos—tiny, unbreakable particles that make up everything. While this was a revolutionary idea, it remained purely philosophical for centuries, with no experimental evidence to support it. The dominant scientific belief, influenced by Aristotle, held that matter was continuous and composed of four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. It wasn’t until the 19th century that atomic theory gained scientific backing. This transition was driven by systematic experimentation, leading to a more concrete understanding of atomic behavior and laying the foundation for particle physics.

The breakthrough came with John Dalton, an English chemist and physicist, who formulated the first scientific atomic theory in the early 1800s. Through experiments on gas behavior and chemical reactions, Dalton observed that elements always combine in fixed ratios, leading him to conclude that matter is made up of indivisible atoms. His theory proposed that each element consists of identical atoms with unique weights and properties, and that chemical reactions involve the rearrangement of these atoms. Dalton’s work provided quantifiable evidence for atoms, shifting atomic theory from philosophical speculation to scientific reality. His discoveries became a cornerstone of particle physics, paving the way for deeper exploration into the nature of matter and atomic structure.

The Discovery of the Electron (1897)

In 1897, J.J. Thomson made a groundbreaking discovery that reshaped the understanding of atomic structure. Using cathode ray tube experiments, he observed that mysterious beams emitted in a vacuum could be bent by both electric and magnetic fields. This behavior suggested that the rays were composed of negatively charged particles, which he named corpuscles, later known as electrons. Through precise calculations, Thomson determined that these particles were far smaller than atoms, directly challenging the prevailing idea that atoms were indivisible. His work provided strong experimental evidence for internal atomic structure, marking a pivotal moment in particle physics and leading to a new understanding of matter’s composition.

To explain his discovery, Thomson proposed the plum pudding model of the atom. In this model, electrons were embedded in a diffuse positive charge, resembling raisins within a pudding. This idea suggested that the positive charge was spread evenly throughout the atom, counterbalancing the negatively charged electrons. His model gained widespread acceptance because it accounted for the known behavior of electric charges within atoms. Additionally, his work paved the way for future discoveries, inspiring physicists to investigate deeper into atomic structure. Though later experiments refined atomic theory further, Thomson’s identification of the electron was a cornerstone in the evolution of particle physics, establishing that atoms were not the fundamental building blocks once believed.

Probing the Nucleus: The Proton (1917)

In 1917, Ernest Rutherford made a groundbreaking discovery that redefined atomic structure by identifying the proton as a fundamental particle within the nucleus. His earlier gold foil experiment in 1909 had already demonstrated that atoms are mostly empty space with a dense, positively charged nucleus at their center. To further investigate this nucleus, Rutherford conducted experiments where he bombarded nitrogen gas with high-energy alpha particles. He observed that hydrogen nuclei were consistently ejected from the nitrogen atoms, leading him to conclude that these hydrogen nuclei were fundamental building blocks of matter. This finding revolutionized particle physics, proving that atoms were composed of smaller, more elementary particles than previously thought.

Rutherford’s identification of the proton was crucial in refining atomic theory. His experiments demonstrated that every atomic nucleus contains at least one proton, which carries a positive charge equal in magnitude to an electron’s negative charge. This discovery provided a clearer understanding of atomic composition and paved the way for the periodic table’s structure, as elements were defined by their proton count. Rutherford’s work not only solidified the proton’s existence but also encouraged further particle physics research, leading to investigations into other subatomic particles. His pioneering experiments set the foundation for later discoveries, including the neutron in 1932, which helped complete the modern model of atomic structure.

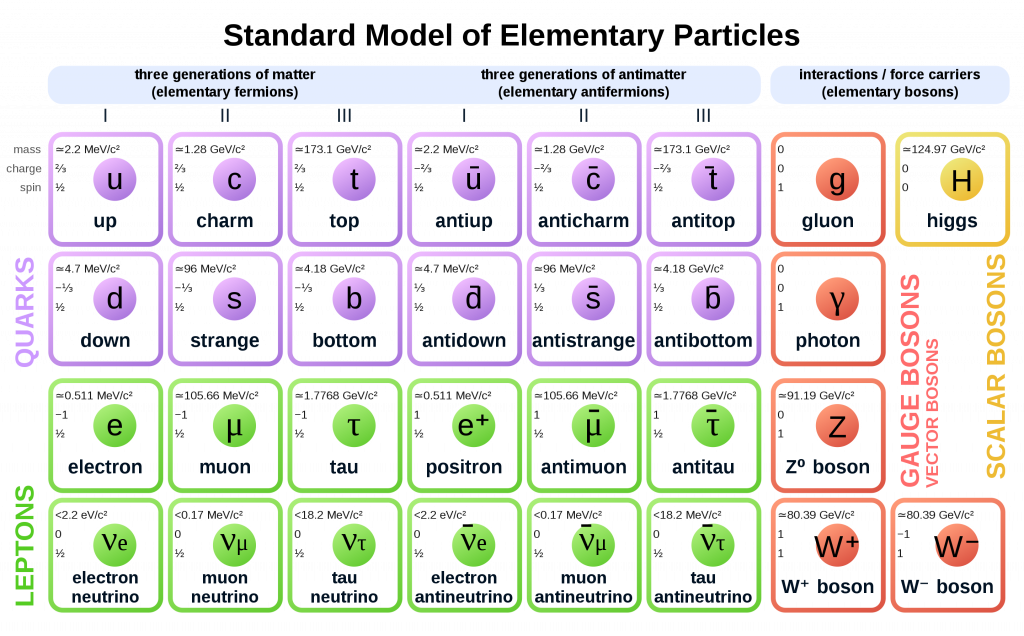

The Standard Model of Particle Physics contains all the known particles and force carriers.

The Discovery of the Neutron (1932)

In 1932, James Chadwick made a landmark discovery by identifying the neutron, a neutral subatomic particle located within the atomic nucleus. He conducted experiments where beryllium was bombarded with alpha particles, leading to the emission of an unknown type of radiation. Unlike charged particles, this radiation did not respond to electric or magnetic fields, suggesting it carried no charge. Chadwick hypothesized that these emissions were made up of neutral particles with a mass similar to protons. His conclusion was experimentally confirmed, revolutionizing particle physics by proving that atomic nuclei contained not just positively charged protons, but also electrically neutral neutrons, which helped explain variations in atomic mass across different elements.

The discovery of the neutron was critical in refining the atomic model and advancing nuclear science. Unlike protons, neutrons do not repel each other due to electric charge, allowing them to act as a stabilizing force within the nucleus. This insight was essential for explaining isotopes, variations of elements with different atomic masses. Chadwick’s work also laid the foundation for nuclear fission, which would later lead to the development of nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. His discovery significantly expanded particle physics, as it opened the door to deeper exploration of nuclear forces and the interactions that govern atomic stability and radioactivity.

The Birth of Quantum Mechanics and the Photon

In 1900, Max Planck laid the foundation for quantum mechanics by studying blackbody radiation, the emission of electromagnetic radiation from heated objects. Classical physics predicted that an ideal blackbody should emit infinite energy at short wavelengths, a problem known as the ultraviolet catastrophe. To resolve this, Planck proposed that energy is emitted in discrete packets, or quanta, rather than a continuous flow. This idea challenged classical wave theory and introduced the concept that light could behave as particles. Planck’s groundbreaking work provided the mathematical framework for particle physics, demonstrating that energy quantization was fundamental to understanding atomic and subatomic processes in nature.

Expanding on Planck’s theory, Albert Einstein proposed in 1905 that light itself is made up of quanta, later called photons. He formulated the photoelectric effect, showing that when light strikes a metal surface, electrons are ejected only if the light’s frequency is above a certain threshold. This proved that light behaved as discrete particles rather than just a wave, contradicting classical physics. Einstein’s theory was later confirmed by Arthur Compton in 1923, who demonstrated that photons could transfer momentum to electrons, validating their particle-like nature. These discoveries were pivotal in particle physics, as they introduced quantum mechanics and reshaped our understanding of energy, light, and fundamental forces.

The Neutrino Hypothesis (1930s) and Confirmation (1956)

In 1930, Wolfgang Pauli proposed the existence of the neutrino to resolve an energy discrepancy observed in beta decay. When certain atomic nuclei underwent radioactive decay, the emitted electron carried less energy than expected, violating the law of energy conservation. Pauli theorized that an undetectable, neutral particle was also emitted to account for the missing energy. He hesitated to publish his idea, calling it a “desperate remedy” since no instruments at the time could detect such a particle. However, Enrico Fermi later expanded on Pauli’s concept, naming it the neutrino and incorporating it into his new framework of particle physics, explaining weak nuclear interactions.

Despite its theoretical importance, the neutrino remained undetected for over two decades due to its extremely weak interaction with matter. In 1956, Clyde Cowan and Frederick Reines successfully confirmed its existence through the inverse beta decay reaction. Using a nuclear reactor as a neutrino source, they observed interactions where neutrinos collided with protons, producing neutrons and positrons—direct evidence of their presence. This discovery validated Fermi’s weak interaction theory and revolutionized particle physics, proving that neutrinos were real and played a crucial role in nuclear processes, stellar reactions, and the formation of the universe itself.

The Rise of the Particle Zoo (1950s-1960s)

During the 1950s and 1960s, advances in particle accelerators and cosmic ray experiments led to the discovery of an overwhelming number of new subatomic particles. Scientists identified numerous mesons and baryons, revealing a chaotic and seemingly unstructured collection of particles beyond the familiar protons, neutrons, and electrons. This rapid influx of discoveries was referred to as the “particle zoo,” as physicists struggled to categorize these new particles within the existing framework. The situation highlighted the need for a more fundamental classification system in particle physics, one that could explain the relationships between these newly found particles and provide a deeper understanding of their internal structure.

In 1964, Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig independently introduced the quark model, which brought order to the particle zoo by proposing that all hadrons (mesons and baryons) were composed of more fundamental building blocks called quarks. According to this model, different combinations of quarks formed the various mesons and baryons observed in experiments. Although initially theoretical, the quark model gained strong experimental support from deep inelastic scattering experiments conducted at SLAC (Stanford Linear Accelerator Center) in the late 1960s. These experiments confirmed the existence of quark-like structures inside protons and neutrons, revolutionizing particle physics and forming the foundation for the Standard Model of fundamental particles.

The Standard Model Takes Shape (1970s-1980s)

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Standard Model of particle physics emerged as the leading framework to describe fundamental particles and their interactions. This model categorized all known particles into three families: quarks, leptons, and gauge bosons. Quarks combined to form protons, neutrons, and other hadrons, while leptons included electrons and neutrinos. Gauge bosons were responsible for mediating the fundamental forces of nature. Experimental breakthroughs played a crucial role in validating the Standard Model, including the discovery of the charm quark in 1974 at SLAC and Brookhaven, followed by the bottom quark in 1977 at Fermilab. Additionally, the tau lepton, a heavier counterpart to the electron and muon, was confirmed in 1975.

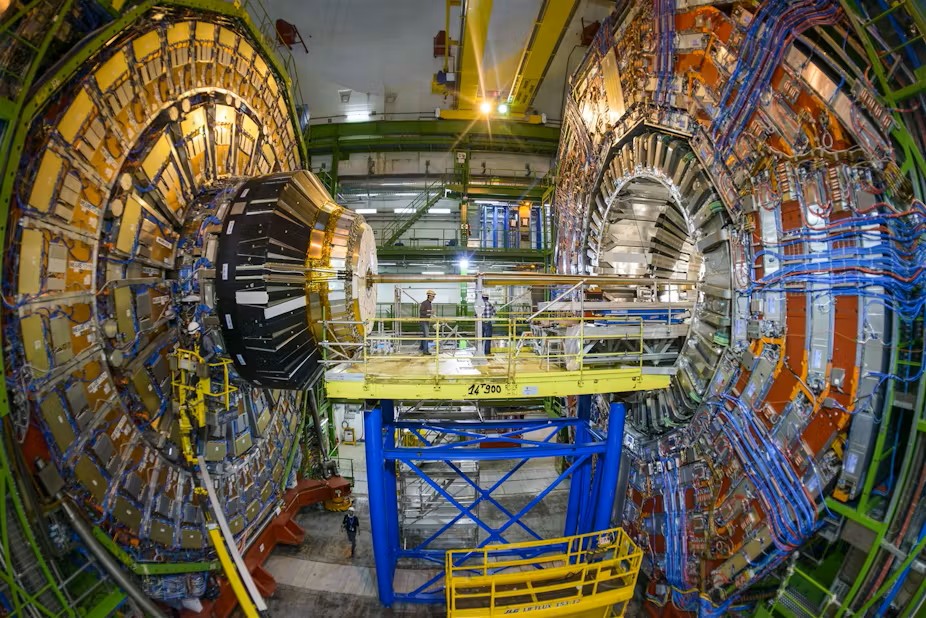

A defining moment for the Standard Model was the discovery of the W and Z bosons in 1983 at CERN. These particles were essential for confirming electroweak unification, which describes the connection between the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces. The discovery was made at the Super Proton Synchrotron, where high-energy collisions produced evidence of these force-carrying bosons. Their detection validated theoretical predictions and cemented the Standard Model as the most successful framework in particle physics. With each experimental confirmation, the model became more refined, providing a deeper understanding of the universe’s fundamental forces and particles, setting the stage for future discoveries such as the Higgs boson.

The Higgs Boson: Completing the Standard Model (2012)

In 1964, Peter Higgs proposed the existence of the Higgs boson as part of a mechanism explaining how particles acquire mass. His theory introduced the Higgs field, an invisible energy field permeating the universe. According to this model, fundamental particles interact with the Higgs field, and the extent of their interaction determines their mass. Particles like photons, which do not interact, remain massless, while others, such as W and Z bosons, gain mass through this process. For decades, the Higgs boson remained purely theoretical, and its confirmation became one of the most sought-after goals in particle physics, driving experimental efforts at particle accelerators worldwide.

The long search for the Higgs boson ended in 2012, when scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) detected its signature. The LHC, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, collided protons at extremely high energies, generating conditions similar to those just after the Big Bang. The discovery was announced on July 4, 2012, confirming the Higgs boson’s mass at approximately 125 giga-electron volts (GeV). This monumental achievement solidified the Standard Model, providing the missing piece to explain mass generation. The significance of this discovery earned Peter Higgs and François Englert the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics, marking a defining moment in particle physics and deepening our understanding of fundamental forces.

The Search for New Physics: Beyond the Standard Model

While the Standard Model of particle physics has successfully explained the fundamental forces and particles that govern the universe, it remains incomplete. One of its biggest shortcomings is its inability to account for dark matter and dark energy, which together make up about 95% of the universe’s total mass-energy. Additionally, the Standard Model does not incorporate gravity, which remains unexplained at the quantum level. Another gap in the model is the unexplained neutrino masses, as it originally assumed neutrinos were massless. These unresolved questions suggest the existence of new physics, leading scientists to search for particles and forces beyond those currently understood.

To address these mysteries, physicists are conducting cutting-edge experiments designed to detect unknown particles. Facilities like LHCb (Large Hadron Collider beauty experiment) analyze rare particle decays, hoping to find deviations from the Standard Model. Meanwhile, neutrino detectors such as IceCube and Super-Kamiokande study neutrino interactions to better understand their properties. Dark matter searches like XENON1T attempt to directly observe dark matter particles, which are believed to interact weakly with normal matter. These efforts aim to push particle physics beyond its current boundaries, potentially leading to new theories that incorporate quantum gravity, supersymmetry, or extra dimensions in the pursuit of a more complete understanding of the universe.

The Future of Particle Physics: Next-Generation Experiments

As the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) approaches its operational limits, scientists are planning next-generation experiments to push the boundaries of particle physics even further. One such project is the Future Circular Collider (FCC), a proposed particle accelerator that would be nearly four times larger than the LHC, allowing for much higher energy collisions. The FCC aims to investigate Higgs boson interactions, dark matter candidates, and possible new forces in nature. Another promising development is the proposal for muon colliders, which would use muons, heavier relatives of electrons, to generate high-energy collisions with significantly reduced energy loss, potentially revealing new physics beyond the Standard Model.

Beyond hardware advancements, emerging technologies like quantum computing and AI-driven data analysis are expected to revolutionize particle physics research. Quantum computers could simulate complex particle interactions, offering new ways to test theoretical models. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence (AI) is enhancing data processing at particle accelerators, allowing scientists to analyze massive amounts of collision data more efficiently. These technologies will help uncover rare events that could signal new particles or undiscovered forces. As next-generation experiments take shape, the future of particle physics holds the potential for groundbreaking discoveries that could reshape our understanding of the universe at the most fundamental level.

The Grand Unification Dream

One of the ultimate goals in particle physics is the development of a Grand Unified Theory (GUT) that unites the electromagnetic, weak, and strong nuclear forces into a single framework. While the Standard Model successfully explains these forces separately, it does not provide a mechanism that connects them at high energy scales. Physicists believe that at extremely high temperatures, such as those present just after the Big Bang, these forces were once a single unified interaction. Theories like Supersymmetry (SUSY) propose that each known particle has a heavier counterpart, potentially solving inconsistencies in current models. Other approaches, like string theory and quantum gravity, aim to incorporate gravity, creating a complete Theory of Everything.

The pursuit of Grand Unification remains one of the most ambitious endeavors in particle physics, as experimental evidence for these theories is still lacking. High-energy experiments, such as those conducted at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), continue to search for supersymmetric particles or other signals of unification. Meanwhile, theoretical advancements in quantum field theory and cosmology guide the search for deeper understanding. The history of particle physics has been defined by breakthroughs that once seemed impossible, from the discovery of the electron to the Higgs boson. As technology and scientific insight advance, the dream of a unified theory remains an exciting and evolving frontier in modern physics.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating / 5. Vote count:

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Author

-

Meet Dr. Kendall Gregory, a highly accomplished professional with a remarkable academic background and a deep passion for empowering individuals through knowledge. Dr. Gregory’s educational journey began with a Bachelor of Science degree, followed by a Doctor of Chiropractic Medicine, focusing on diagnosing and treating musculoskeletal conditions. He further expanded his expertise with a Master's degree in Oriental Medicine, specializing in acupuncture and Chinese herbology, and a Master's degree in Health Care Administration, emphasizing his dedication to improving healthcare systems. Dr. Gregory combines his extensive knowledge and practical experience to provide comprehensive and integrative healthcare solutions. Through his writings, he aims to inspire individuals to take charge of their health and make informed decisions.

View all posts