Table of Contents

Early Life and Education

Born in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, in 1643, Isaac Newton entered the world under difficult circumstances, arriving prematurely and without a father, who had died three months prior. His mother later remarried, leaving him in the care of his grandmother. Despite these challenges, he displayed an early passion for mechanics, crafting functional sundials, windmills, and water clocks. His academic journey began at The King’s School in Grantham, where he excelled in mathematics and Latin. When his mother withdrew him from school to become a farmer, his disinterest in agriculture was clear. A teacher recognized his potential, persuading his mother to allow him to continue his education, a decision that altered the course of scientific history.

At Trinity College, Cambridge, he immersed himself in the works of Aristotle, Descartes, and Galileo, absorbing classical and contemporary knowledge that would later fuel his groundbreaking discoveries. Initially attending Cambridge as a student who worked to pay tuition, he soon stood out for his brilliance in mathematics and natural philosophy. While university teachings still adhered to Aristotelian principles, he sought deeper truths through personal study, exploring advanced mathematical theories and physics. His early notebooks, filled with observations and mathematical problems, reflected an inquisitive mind far ahead of his time. These formative years played a crucial role in shaping the theories that revolutionized science, setting him on a path that would redefine humanity’s understanding of motion, optics, and gravity.

The Plague Years and the Annus Mirabilis

In 1665, the Great Plague swept through England, forcing Cambridge University to shut its doors and sending scholars home. Isaac Newton returned to Woolsthorpe, where isolation became a period of extraordinary intellectual achievement. Over the next two years, he made groundbreaking discoveries in calculus, a mathematical system that would later become fundamental to physics and engineering. His work established methods for calculating rates of change and areas under curves, revolutionizing problem-solving in mathematics. During this same period, he conducted experiments with prisms, demonstrating that white light is composed of multiple colors, contradicting the prevailing belief that prisms merely colored light rather than separating its inherent spectrum.

His time away from university also led to major breakthroughs in physics, particularly regarding motion and gravity. Observing an apple fall from a tree, he theorized that the same force governing objects on Earth also controlled celestial bodies. This realization laid the foundation for his law of universal gravitation, explaining planetary orbits with mathematical precision. Without distractions or external pressures, he worked tirelessly to refine his theories, unknowingly shaping the course of modern science. Even before formally publishing his findings, his ideas were so advanced that they secured his place among history’s greatest thinkers.

The Invention of Calculus

During the late 17th century, mathematical advancements were essential for solving complex problems in physics and astronomy. Isaac Newton developed a system of differentiation and integration, which he called the “method of fluxions,” allowing scientists to calculate instantaneous rates of change. This breakthrough provided the necessary mathematical framework for describing motion, acceleration, and forces, making it indispensable to physics and engineering. His discoveries enabled precise calculations for planetary orbits, fluid dynamics, and structural mechanics. Although his work remained largely unpublished for years, he had formulated the principles of calculus before any known counterpart, shaping the way mathematical analysis would be applied in the natural sciences and technological advancements.

Despite these achievements, his claim to calculus sparked a lasting controversy. German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz independently developed and published a similar system in 1684, using a notation that became more widely adopted in Europe. Although Newton had formulated his version earlier, the lack of immediate publication led to an intense rivalry. The dispute escalated when members of the Royal Society, influenced by his authority, accused Leibniz of plagiarism. This intellectual battle divided mathematicians for decades, delaying collaboration between British and European scholars. Today, both men are credited for their contributions, as modern calculus incorporates elements from both systems, forming the foundation of advanced mathematics worldwide.

Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitation

In 1687, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica introduced a mathematical foundation for understanding motion and force. Isaac Newton’s three laws of motion established fundamental principles that explained the behavior of objects in motion. Isaac Newton’s first law, known as the law of inertia, states that an object remains in uniform motion or at rest unless influenced by an external force. The second law quantifies this force, showing that acceleration is directly proportional to force and inversely proportional to mass. His third law, often summarized as “for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction,” explains interactions between objects, influencing mechanics, engineering, and even the physics of rocket propulsion and space travel.

His work extended beyond motion, introducing the law of universal gravitation, which explained how objects attract each other based on mass and distance. The same force that causes a falling apple to accelerate toward Earth also governs planetary motion, ensuring celestial bodies follow predictable orbits. Using precise mathematical calculations, he confirmed Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, demonstrating that gravitational attraction maintains planetary paths. This breakthrough revolutionized astronomy, providing a framework that allowed future scientists to calculate planetary trajectories, predict comet paths, and understand tidal forces. His principles remain central to classical physics, guiding scientific advancements for centuries and shaping modern understanding of gravity and motion.

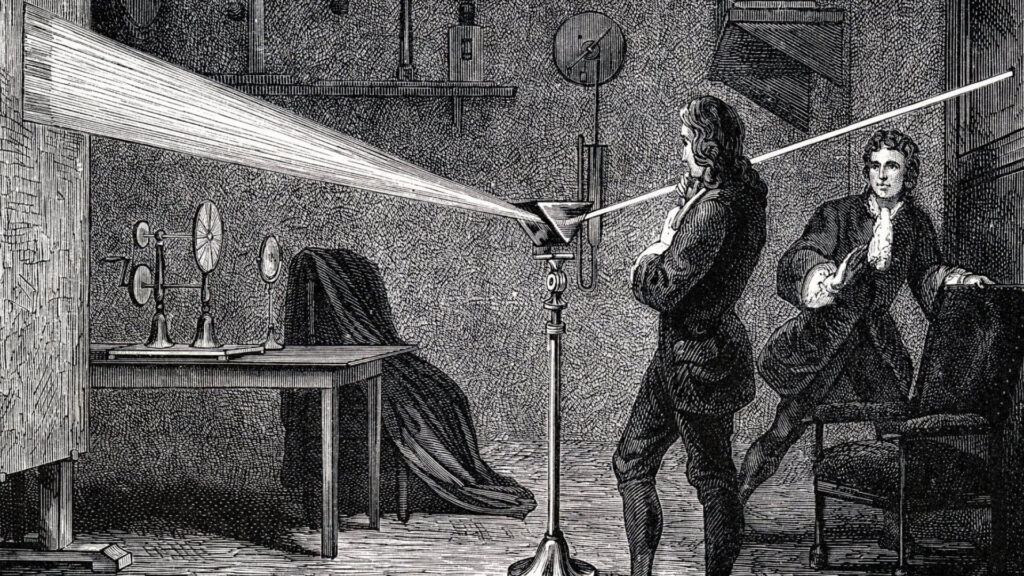

Newton and Optics: The Nature of Light

Through meticulous experimentation, Isaac Newton revolutionized the understanding of light and color, ultimately publishing his findings in Opticks (1704). By passing a beam of sunlight through a glass prism, he demonstrated that white light was not a singular entity but rather a combination of multiple colors. This discovery refuted the long-standing belief that colors were mere modifications of white light. He further showed that these separated colors could be recombined to form white light again, proving that color is an intrinsic property of light itself. His experiments established a new foundation in optics, shifting scientific thought away from Aristotelian ideas and toward an empirical, physics-based explanation of light’s behavior.

Beyond his color experiments, he introduced the particle theory of light, proposing that light consisted of small, fast-moving particles, or “corpuscles.” This idea challenged the prevailing wave theory supported by figures like Robert Hooke. While later discoveries, such as Thomas Young’s double-slit experiment, provided strong evidence for the wave nature of light, aspects of his particle theory resurfaced in the early 20th century with quantum mechanics. The concept of photons, developed through Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect, validated the idea that light behaves both as a particle and a wave. His research in optics laid the groundwork for modern physics, influencing fields such as spectroscopy, photography, and fiber-optic communications.

The Principia and Its Impact on Science

In 1687, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica established a mathematical framework that transformed the study of motion and gravity. Within its pages, Isaac Newton formulated the laws governing planetary movement, offering precise explanations for Kepler’s laws. He demonstrated that celestial bodies followed elliptical orbits due to gravitational forces, unifying physics and astronomy under a single set of principles. His rigorous application of mathematics to natural phenomena allowed scientists to predict planetary motion with unprecedented accuracy. This marked a turning point in scientific thought, shifting from philosophical speculation to mathematical precision. His work provided the foundation for engineering, navigation, and the understanding of natural forces governing the universe.

The influence of Principia extended far beyond Newton’s lifetime, shaping the course of scientific progress for centuries. His laws of motion and gravity formed the backbone of classical mechanics, guiding technological advancements from industrial machinery to space exploration. The precision of his equations enabled future scientists to calculate planetary trajectories, leading to the successful landing of spacecraft on distant worlds. Even Albert Einstein, whose theory of relativity refined gravitational understanding, acknowledged the immense impact of Newtonian physics. Though later theories expanded upon his work, the principles outlined in Principia remain essential, underscoring his role as one of history’s greatest scientific minds.

Newton’s Later Career and Role in the Royal Society

n 1672, Isaac Newton was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, an institution dedicated to advancing scientific knowledge. His contributions in mathematics, physics, and optics made him one of its most influential members. In 1703, he ascended to the presidency, a position he held for over two decades. Under his leadership, the society became the epicenter of scientific discovery in Europe, attracting the brightest minds of the era. However, his tenure was marked by fierce rivalries, particularly with Robert Hooke and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. He often used his influence to suppress competing theories, ensuring that his own discoveries remained dominant in the scientific community.

Beyond his scientific leadership, he played a crucial role in England’s financial stability as Warden of the Royal Mint, a position he assumed in 1696. Tasked with overseeing the nation’s currency, he aggressively pursued counterfeiters, personally leading investigations that resulted in numerous convictions. His meticulous approach to refining the minting process helped restore confidence in England’s monetary system. In 1699, he was promoted to Master of the Mint, a role he held for the rest of his life. His work in this field demonstrated his ability to apply mathematical precision not only to science but also to economic policy, securing his legacy beyond the realm of physics.

The Newton-Leibniz Controversy

The debate over calculus remains one of the most contentious disputes in the history of mathematics. Isaac Newton had developed his method of fluxions in the mid-1660s but delayed publishing his findings. Meanwhile, German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz independently devised a similar system and published his work in 1684. Since Leibniz’s notation was more accessible and widely adopted in Europe, suspicions arose regarding whether he had borrowed ideas from Newton’s unpublished work. The Royal Society, under Newton’s leadership, launched an investigation and ultimately ruled in his favor. However, this inquiry was biased, as Newton himself had secretly written much of the committee’s final report, ensuring an outcome that discredited his rival.

This prolonged controversy created a rift within the mathematical community, dividing scholars into Newtonian and Leibnizian factions. The dispute became so personal that it hindered collaboration between British and European mathematicians for decades, delaying mathematical progress. Despite their rivalry, modern historians acknowledge that both men arrived at calculus independently, and their respective approaches—Newton’s fluxions and Leibniz’s differential notation—form the foundation of integral and differential calculus used today. While Newton’s contributions advanced physics, Leibniz’s notation became the standard in mathematical analysis. This conflict illustrates the competitive nature of scientific discovery and the lasting impact of intellectual disputes on academic advancement.

Newton’s Religious and Alchemical Interests

Throughout his life, Isaac Newton maintained a deep fascination with religion, considering his scientific discoveries as evidence of a divine creator. He was intensely interested in biblical prophecy, believing that the universe operated under laws set forth by God. His rejection of the doctrine of the Trinity placed him at odds with mainstream Christianity, leading him to keep many of his theological beliefs private. He meticulously analyzed religious texts, searching for hidden meanings and prophetic insights. Unlike many scientists of his era, he saw no conflict between faith and reason, instead viewing natural laws as proof of a divine order governing the cosmos. His theological writings, though lesser known, reveal a mind devoted to understanding both science and spirituality.

Beyond religion, his interest in alchemy occupied much of his time, with thousands of pages dedicated to its study. He sought the legendary philosopher’s stone, believed to have the power to transform base metals into gold and grant immortality. While modern science dismisses alchemy as pseudoscience, his experiments with chemical transformations influenced early developments in chemistry. His studies of metals and compounds reflected an intense curiosity about the fundamental nature of matter. Though alchemy never yielded the results he sought, the meticulous experimental methods he used mirrored his approach to physics, demonstrating his relentless pursuit of knowledge across all fields of inquiry.

The Legacy of Newtonian Science

Few individuals have shaped the course of scientific thought as profoundly as Isaac Newton. His laws of motion and universal gravitation laid the foundation for classical mechanics, providing a framework that governed physics for over two centuries. These principles allowed scientists to accurately describe planetary orbits, projectile motion, and the mechanics of machines. His influence extended beyond physics, as his approach to mathematical precision in problem-solving became the gold standard for scientific inquiry. It wasn’t until Albert Einstein introduced theory of relativity in the early 20th century that Newton’s gravitational model required modification. Despite this, his equations remain essential for modern engineering, space exploration, and everyday applications such as satellite navigation.

His contributions to optics, mathematics, and experimental methodology redefined how science was conducted. By emphasizing rigorous empirical observation, he demonstrated that scientific truths must be tested and verified, an approach that continues to guide modern research. His advancements in calculus provided powerful tools for modeling natural phenomena, influencing disciplines from astronomy to economics. The structure of modern physics, engineering, and technology owes much to his discoveries. Even in today’s era of quantum mechanics and relativity, many technologies—from mechanical engineering to orbital mechanics—still rely on Newtonian principles, underscoring his lasting impact on the scientific world.

Final Years and Death

As his career progressed, Isaac Newton gradually stepped away from active scientific research, devoting more time to his administrative roles. As President of the Royal Society, he oversaw scientific advancements and maintained his influence over European intellectual circles. His position as Master of the Royal Mint also remained a priority, where he continued efforts to reform England’s currency. By this time, he had become a national figure, revered not only for his contributions to physics and mathematics but also for his role in stabilizing the economy. Despite withdrawing from theoretical work, he remained an authoritative voice in science, ensuring that his discoveries shaped the next generation of scholars and researchers.

During his later years, he endured kidney stones and digestive ailments, which caused periods of great discomfort. However, his mind remained sharp, and he continued to engage in discussions on science and philosophy. On March 31, 1727, he passed away at the age of 84, marking the end of one of the most influential scientific careers in history. His burial in Westminster Abbey was a testament to the profound impact he had on human knowledge. Though centuries have passed, his principles remain fundamental in modern physics, ensuring that his legacy continues to inspire scientists, engineers, and scholars around the world.

Newton’s Enduring Influence

Few scientific figures have left a legacy as profound as Isaac Newton, whose principles continue to underpin modern science and technology. His laws of motion and universal gravitation remain central to physics education, forming the basis for engineering, mechanics, and space exploration. His work extends beyond theoretical physics, as the mathematical techniques he developed, including calculus, are widely applied in fields such as economics, computer science, and engineering. Modern astrophysics relies heavily on Newtonian mechanics, particularly in calculating planetary orbits and spacecraft trajectories. Even with advancements like quantum mechanics and relativity, his principles are still used in designing bridges, predicting weather patterns, and developing cutting-edge technologies across multiple disciplines.

His influence is not limited to equations and theories but extends to the scientific method itself. By emphasizing empirical observation, experimentation, and mathematical reasoning, he helped establish the foundation for modern scientific inquiry. These principles guide research across fields, from medical advancements to artificial intelligence. While later scientists such as Einstein expanded upon his theories, his work remains a crucial stepping stone in understanding the physical world. Whether in engineering, space travel, or technological innovation, his discoveries continue to shape the way humanity understands and interacts with the universe, ensuring that his contributions remain relevant centuries after his passing.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating / 5. Vote count:

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Author

-

Meet Dr. Kendall Gregory, a highly accomplished professional with a remarkable academic background and a deep passion for empowering individuals through knowledge. Dr. Gregory’s educational journey began with a Bachelor of Science degree, followed by a Doctor of Chiropractic Medicine, focusing on diagnosing and treating musculoskeletal conditions. He further expanded his expertise with a Master's degree in Oriental Medicine, specializing in acupuncture and Chinese herbology, and a Master's degree in Health Care Administration, emphasizing his dedication to improving healthcare systems. Dr. Gregory combines his extensive knowledge and practical experience to provide comprehensive and integrative healthcare solutions. Through his writings, he aims to inspire individuals to take charge of their health and make informed decisions.

View all posts

[…] of space-time would inflate at different rates, creating isolated bubble universes with unique physical laws. Some of these universes may have collapsed instantly, while others could be dominated by extreme […]